8.2. Total cost of ownership and moving to high capital, low operational costs

Switching to EVs can involve higher upfront costs but lower operating expenses. Considering total ownership costs, adjusting replacement cycles, and using carbon costing can cut long-term fleet costs and emissions.

EVs cost more to buy or lease but less to operate than conventional internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles. You should assess the viability of EVs by considering all costs over the vehicle’s lifetime.

You may want to adapt vehicle replacement cycles and procurement processes. This can help reduce the cost of decarbonising, which means you’ll save on fleet costs in the long term.

Total cost of ownership

Total cost of ownership, or whole life cost, is the total cost of owning and operating a piece of equipment throughout its life cycle. This includes the upfront cost of buying or leasing the equipment and the ongoing operational costs.

Moving to a decision-making process that considers the total cost of ownership may require a shift in behaviour. But it is key to adopting a sustainable system. More sustainable options – whether they use ethical materials, have lower energy use or emissions, or include replaceable and repairable parts – tend to have higher upfront costs but lower operational costs over their lifespan.

Adapting fleet replacement cycles

As diesel and petrol engines age they deteriorate, emitting more greenhouse gases and air pollution. EVs don’t deteriorate in this way, so keeping them in use longer won’t increase emissions.

As the UK grid decarbonises EV emissions will fall year on year, without any changes to the vehicles. This means the higher upfront costs of an EV can be spread over a longer period of ownership. Aside from spreading the cost, longer periods of ownership also allow more use of the energy and resources that go into manufacturing the vehicle, especially the battery.

To maximise return on investment, align EV replacement cycles with the vehicle’s battery warranty. If a battery is well maintained, it could last much longer than its warranty period. This may mean you can plan replacement cycles of seven or eight years or even up to ten years.

Carbon costing

Carbon costing involves putting a price on emissions to measure the damage caused by a pollutant. The polluter then pays to fix that damage.

The UK Government uses greenhouse gas emissions values (or ‘carbon values’) to evaluate the impact of policy changes on the environment. The UK Treasury Green Book has guidance on the policy and project appraisal framework, including carbon valuation, to ensure the best public value.

Although carbon taxes may not be formally paid, they can be used internally to address your organisation’s impact on public health and the environment. You could implement a carbon tax on your processes and use the money collected to buy more sustainable or zero-emission equipment. For example, you could introduce a £0.05/mile levy on your ICE vehicles and put the money towards buying EVs and charging infrastructure.

Putting a price on emissions, even if no money is exchanged, is known as a ‘shadow price’. Including these costs on your financial statements shows the extent of harm compared to your income and outgoings. This might be a more meaningful way to discuss pollution than using terms like weight or tonnes of carbon dioxide, which are hard to grasp.

Procurement

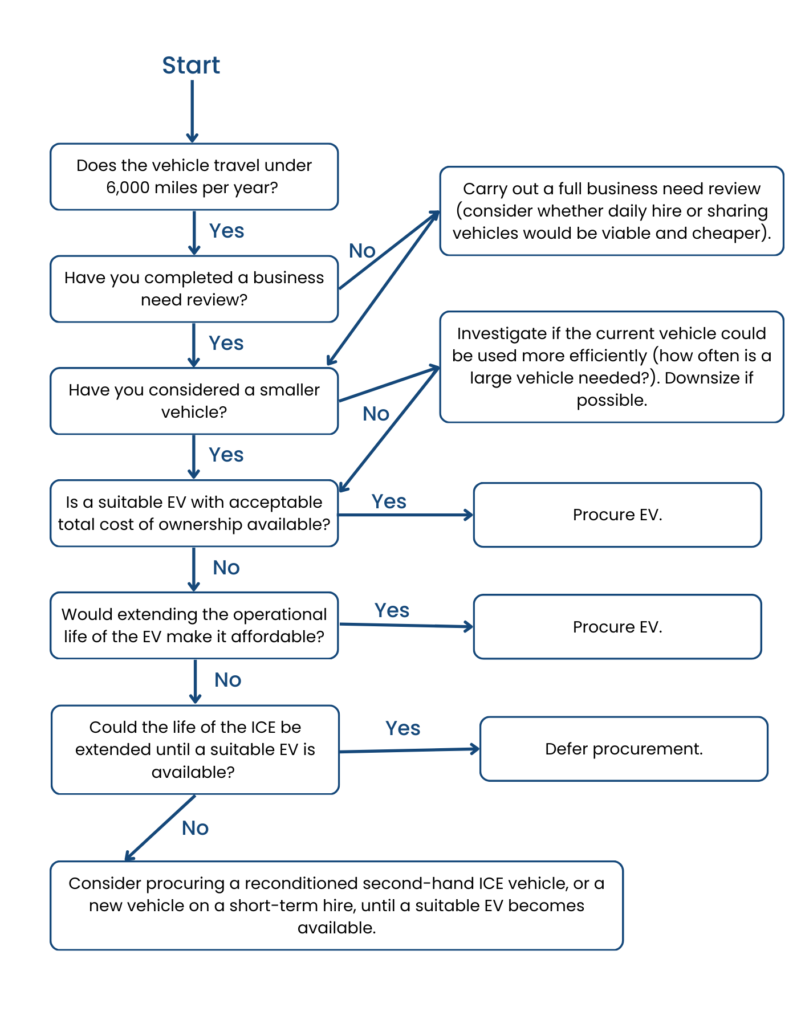

You should remove any barriers to procuring EVs. EVs should become the default choice where they can meet your operational needs. If an EV can do the job, then any requests for ICE vehicles should be challenged. The following diagram outlines this process: from assessing the need for a vehicle to procuring an EV as default or considering other options.